Computation and cognition of Holon Gardens

Rambling about a new paradigm for our Civilization.

Global socio-technical systems require a new type of technology that enables harmonious collectiveness and collaboration. Holon Gardens is an early version of an innovative technology natively conceived to be collective, that we are calling a collective computer. The potential of this technology is transformative as it enables new forms of social organization and unlocks new horizons in engineering design, management, and products as it expands the space and scale of potential integrations now hidden or out of reach to traditional engineering and management methods.

Decision making and collaboration within collective systems is a critical issue for both global-scale socio-technical problems, and an existential consideration for many specific and concrete problems that affect individuals and smaller initiatives.

Take for example two different teams during the engineering and business design of a new product. The resolution of tensions produced by technical paradoxes, different priorities, variety of disciplinary perspective, or personal agendas is something traditionally left to processes that rely on hierarchy, authority, standardization or centralization. All those methods struggle to scale when dealing with complex systems that don’t have a center, authority or standard.

Furthermore, even traditional engineering and manufacturing integration is struggling in a world of complexity and uncertainty at scale, take the example of the brand new Boeing 737 Max 9 airplane which got a panel detached from the fuselage during a flight of Alaska Airlines in 2024. Collectiveness and integration matters for global and strategic reasons like democracy and corporate decision making, and also for practical life or death situations with traditional systems like integrating panels to airplane fuselages. Or the recent accident at Washington, DC, where a commercial airplane collided with a military helicopter killing all 67 aboard of both aircraft. How is it possible that with all modern technology we still see these coordination problems?

Holon Labs Foundation believes that a new technology natively conceived and developed as a collective system needs to emerge in order to address these issues of collective coordination. We call this new technology a collective computer.

In order to progress the philosophy, science and technology that will allow collective computers to emerge we follow an experimental path in which we are trying to cognitively intervene in different collective systems to enhance harmony and coordination. Gardens provide a perfect laboratory for collective systems given the paradoxical tension between their origin: a need for control and containment of nature with their reality, and their intertwined existence with all in a local environment.

Gardens, as a place in which humans have attempted to control nature, have historically played a significant role in driving the development of science and philosophy together with culture and aesthetics. A prime example of gardens being involved in scientific discoveries is when Gregor Mendel, considered the "father of modern genetics", conducted his famous study of variation in plants in his monastery's 2 hectares (4.9 acres) experimental garden. The philosophy behind gardens has been mostly about control and management of nature, about enclosement, property, productivity, and many of the core aspects of a modern society that values an analytical mindset, a productive industrial intent, and a human-centric and hierarchical view of the world.

We believe that modern collective Holon gardens can be the platform in which a new type of experimentation occurs; one that is more phenomenological than analytical; that combines the individual with the collective; that considers cognition as embodied.

A technology that allows different neighbors to collaborate amongst themselves, and also with the ecology in which the gardens exist, is the same technology that allows musicians to collaborate with the box office staff of a city symphony/orchestra, and the same technology that allows multiple stakeholders of water systems to collaborate with water itself and its infrastructure and local environment. The use of sticks for digging are an example of early technology in gardening.

Gardens can be a source of health, resilience and productivity, such that we expect many institutions and initiatives to support and sponsor this initiative. We also expect that Holon Gardens will become a state of the art community-driven laboratory for scientific and technological innovation from which many collateral innovations are going to emerge and develop.

Context

Gardens are an important feature of many homes, neighborhoods and almost any urban and rural system. They have been historically important in many cultures for their aesthetic function, as a symbol of social status, and for many people as a source of joy for the direct relationship they establish with nature.

But the relationship that gardens provide with nature is one of control and dominance. One of order over chaos. In fact, the etymology of the word gardening refers to enclosure, referring to an area that is sealed off with an artificial or natural barrier.

But no garden is truly enclosed. Depending on the style, like french formal gardens, they could require expensive and constant human effort for maintenance, forcing humans to prune all trees, shrubs, and lawns regularly to maintain - strict, manicured shapes. Paradoxically, by attempting to control nature humans end up enclosing themselves into slaves of their gardens instead of partnering with them in a symbiotic relationship.

Gardens tend to be perceived as ornamentals or decorative. These ideas are not new, and our understanding of what gardening means comes from multiple historical trajectories. Philosopher Shaftesbury famously discussed the concept of physical beauty to be features of the natural world, contrasting the beauty of french formal gardens, and arguing for the superiority of naturalness or wildness over the artifice and “formal Mockery of princely Gardens” (C 2.393–4). But seeing gardens as merely ornamental was not only about beauty but about believing that human intelligence was above the intelligence of nature. The order and control given to french gardens was a display of how much better humans could do than nature which was associated with chaos, messiness, dirt, plagues and many other undesirable natural states. As described by Lucia Impelluso, Jardins, potagers et labyrinthes, pg. 64.: "The views and perspectives, to and from the palace, continued to infinity. The king ruled over nature, recreating in the garden not only his domination of his territories, but over the court and his subjects."

Jim Endersby, Professor of the history of science at the University of Sussex and Gresham College, has a fascinating take on the relationship between gardens and our cultural aspirations, describing how our relationship to gardening, particularly european gardens, has influenced the trajectory of many beliefs and ideas that shape our technological and industrial present.

Japanese gardens, similarly but in a different direction, have also become this traditional symbol of a culture that is also a philosophical device that comes with aesthetics, ideas and practices that define our world. One important idea that is highlighted in many japanese gardens, is impermanence and the fragility of the natural world, which is a notable contrast with the attempts to control Nature and minimize its uncertainty that is seen in traditional British or French gardening systems.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) was one of the most influential scientists and thinkers of his age. A Prussian-born geographer, naturalist, explorer, and illustrator; he visited the United States engaging in a lively exchange of ideas with such figures as Thomas Jefferson. His artistic representations of the landscapes of the United States helped to shape an emerging American identity grounded in the natural world. His profound understanding of nature as an interconnected web, coupled with his vivid depictions of diverse natural landscapes, fostered a new appreciation for wild beauty that indirectly influenced gardening and landscaping. His scientific observations on plant geography informed the selection and arrangement of plants in gardens, while his warnings about human impact on the environment contributed to a growing ethos of sustainable practices. By inspiring landscape artists and shifting aesthetic preferences towards naturalism, Humboldt's holistic view of the environment laid a foundational influence on creating gardens and landscapes that were more ecologically aware, aesthetically natural, and reflective of the interconnectedness he so eloquently described.

Indigenous communities have been doing this around the world for a long time, often holding a deep and reciprocal relationship with both gardening and the soil, viewing them as living entities rather than mere resources. Gardening was frequently intertwined with spiritual practices, community well-being, and the cyclical rhythms of nature, with the soil considered a sacred and nurturing mother. Traditional knowledge systems encompassed intricate understandings of soil types, fertility, and sustainable cultivation practices passed down through generations, emphasizing minimal disturbance, crop diversity, and the integration of ecological principles to ensure long-term health and productivity of the land. This holistic perspective fostered a profound respect for the soil as the foundation of life, influencing agricultural practices that prioritized harmony with nature and the sustenance of future generations.

In Holon we like to think about gardens as portals to the whole. An entrance that we as individuals have to the whole around us, our neighborhoods, cities, ecology and ultimately to our whole self. Gardens, especially for us who live in urban systems, have the potential to be our first embrace of nature.

Gardens are collective multitudes in themselves. They contain a diversity that shouldn’t be constrained but embraced in all its plurality.

Our orientation as we design and build gardens, is towards first, formally configuring the affordances within gardens enables them to behave as cognitive collective systems. A potential approach to establish material formality is to consider design strategies of board games and role-play games at a community level in which each garden is a piece or stage of the game; second, the collectiveness between gardens transcends humans and should include buildings, the weather, insects, mycelium, animals, rocks, water bodies; third, the fact that gardens present constructive tension and ambivalence between private property and community spaces; and fourth, that the focus on local species can contribute to ecological restoration and remediation even when climate change and other factors are threatening their existence.

Gardens for Holon, as complex systems, should have no objective or function in order to be truly collective systems, which means to acknowledge the multitude of functions attributed from different perspectives to these systems. Some of them are:

Traditional functions of community gardens beyond collective computing

Gardens as a source of community

Community gardens are not a new concept. In fact, we have seen a massive proliferation just in the US with gardens such as the Cherryhurst vertical garden in the Montrose neighborhood in Houston Texas, managed by our Chief Regenerative Office, Flora Moon.

These gardens function as a critical source of community building which addresses what the Surgeon General of the United States, Dr. Vivek Murthy called in 2023 an “epidemic of loneliness” and suggested a call to action to address what he considered a public health crisis.

In fact, it has been observed that the act of gardening and connection with the soil has significant positive implications in health and life expectancy.

Community gardens are a perfect example of what American sociologist Ray Oldenburg described in the 1980s as "third place: a space for informal, free social interaction, essential to democracy.” These spaces can provide something like an ecological-social credit that gives status and belonging to individuals within communities.

Some Community Garden Statistics for 2024:

Community gardens increase surrounding property values by up to 9.4%.

Average community garden yields about 20.4 servings of fresh produce per 11 sq. ft.

Community gardens can lower household food security concerns by up to 90%.

Every $1 invested in a community garden yields around $6 worth of produce.

Community gardens have a positive impact on neighborhood security.

There are over 29,000 community gardens in the 100 largest U.S. cities.

Community gardeners eat 37.5% more fruits and vegetables than non-gardeners.

Common reasons for garden participation are access to fresh foods, health benefits, and to enjoy nature.

Women community gardeners are 46% less likely to be overweight than their neighbors.

Gardens as a collective form of art

A collective computer, by definition, creates collectives as it computes experiences and phenomena. The results of a collective computation resemble the processes artists use to experiment with the concept of a collective creation. A garden is a specific, although incredibly flexible and expansive, form of material and medium in which art can be performed and created.

There are many examples in art in general of collective expression, varying from installations in which visitors interact and change the art; art that invites participation in the propagation of consequences over the whole system that happen after each individual action. Collective forms of art like this illustrate the physical interconnection of systems, making explicit structural relationships that are not always visible.

Collective art can also take the form of narratives or literature mixed with visual arts, or approaches in which the rules of many of these collective forms of arts are not always completely clear or enforceable. This means there are participants who either don't understand or don't abide by the instructions. It is not uncommon for participants in collective art exhibitions to instead write notes directly to the readers or perform actions that violate the collective behavior or agreement. This behavior will be expected and normal in an unregulated and truly collective form of garden.

Collective creations can also be a collective composition as contributions by each individual change forever the nature of the piece. Through this, the public and the garden—composed together—become the art.

A particular example of a collective form of art is the work done by indigenous communities in South America, called the Kipu or Quipu. This artwork is relevant to collective gardens behaving as collective computers or collective cognitive systems as they also functioned as a form of collective language and communication that the artist Cecilia Vicuña recreated in her piece Brain Forest Quipu for the Tate Modern in London. This piece is a multi-part installation made up of sculpture, sound, music and video. The quipu is an ancient South American recording and communication system made from knotted threads. At the center of Brain Forest Quipu are two sculptures that hang 27 meters from the ceiling. They are woven together using a range of organic materials, including found objects, unspun wool, plant fibers, rope and cardboard to evoke the look of bleached-out trees and ghostly forms. This is a uniquely collaborative project with Vicuña working alongside artists, activists and members of the community. Some of the items used in the sculptures have been collected from the banks of the Thames by women from local Latin American communities. Vicuña created the soundscape with Colombian composer Ricardo Gallo. It brings together Indigenous music from around the world, Vicuña’s own voice and music from fellow artists, alongside field recordings of nature and moments of silence.

“The Earth is a brain forest, and the quipu embraces all its interconnections,”

- Cecilia Vicuña

Collective gardens are also a unique space for humans to interact with other species and forms of life. In September 2023, Cookie, Sophus, and Sica—three dogs—performed with the Danish Chamber Orchestra in a rendition of "Hunting Symphony," by Leopold Mozart, the father of Wolfgang Amadeus. The symphony features barking dogs, hunting calls and simulated gunshots by a percussionist. Leopold Mozart called this addition of animals to his compositions “naturalism”. The collaboration with nature, through animals, fungi, plants or other species brings about the questions of attribution, ownership and property, value, recognition and compensation among many others. Collective creations with non-human entities also brings about the questions of control and repeatability. The specific piece performed by the dog's barking will be significantly different every time it is performed. One could argue that any musical performance is different every time that is performed live, but dogs barking bring this variability to a whole new level.

The Houston Zoo also has a program in which the zookeepers work to “enrich the lives of the animals in their care every day by introducing fun, interesting, and complex activities, such as painting, to the animals’ daily routine”. The creations by the animals can then be purchased by people, which goes towards supporting the Zoo and the city. The paintings by the animals can be found across the city like in the halls of the Houston Methodist Hospital and other places.

Japanese Zen Gardens provide a unique aesthetic approach to gardening, in which contemplation, reflection and the projection of symbolizing a deep philosophy through the material expression given by the configuration of rocks, plants, water and other components, all together in harmony that provide a composed emergent effect.

Gardens are also attached to infrastructure like walls, fences, benches, buildings, and other human-made systems that can become composed with the garden through expressions of art. We envision collective forms of art like graffiti to naturally become a decorative aspect of these gardens. Examples like graffiti knitting or yarnstorming or yarnbombing or guerrilla knitting is the art of using items handmade from yarn to create street art.

Gardens are also physical open spaces in which forms of performance art can emerge. Dances, singing, conceptual art and others can become part of these collective spaces.

We also expect the emergence of collective themes in each garden and neighborhood to embrace and develop specific forms of aesthetic, or symbols, or colors that produce a collective identity that is so essential in the production of compositional collectiveness.

Sculptures play a key role in collective gardens as they can act as material forms of expressions that can add to the form and function of each garden.

Designer Cas Holman has developed the concept of collective playgrounds in which she has re-imagined the archetypal playground and designed a mobile storage unit to translate the playground into a “pop-up." It can now be found in schools, children's museums, and playgrounds around the world.

Gardens as a collective commercial and productive system

Collective gardens like community gardens are already becoming critical productive systems for neighborhoods and people around the world. They already produce several of them and they have the potential to become more and more a formal mechanism of increased income.

Food like vegetables and fruits, honey and even meat and eggs depending on the affordances of each garden and community.

Enable small scale farming and agriculture

Soil is slowly but promisingly becoming a source of energy, in which companies like biootech.com are already commercializing the opportunity to activate soil and gardens to gather energy

Public space is limited and expensive in urban systems so collective gardens could become opportunities to allow temporary or permanent use of space for commercial purposes

Collective gardens can be collective in the relationship between individual households who are hosting the garden and commercial entities as a form of farm to table enterprises (food coops/restaurants)

Gardens are the ultimate form of multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder systems, as they force us to include many types of perspectives and forms of life. This type of hyper collaboration and integration promises to transform all industries that deal with complex systems.

A mechanism for public/guvernamental action in which governments, municipalities, homeowner associations and other institutions can direct resources to support the individual efforts that benefit the collective system. These mechanisms could evolve to become taxes or direct monetary incentives for their effects in carbon capture, water absorption, biodiversity remediation, and many other ecological implications that benefit and protect the interests of nations and humanity in general.

Collective gardens can be laboratories for researchers in biology, sociology and other disciplines in which small payments can be made to the host for the use or activation of these spaces.

Gardens as a collective ecological action

The Homegrown National Park initiative is a great example of a collective effort as a grassroots call-to-action to regenerate biodiversity and ecosystem function by planting native plants and creating new ecological networks. They use digital tools to create the connective tissue between the different gardens. We instead want to use phenomenological and analog technologies to enable compositional collectiveness.

The intervention of gardens to enhance the relationship with their ecological context is not a new thing. Terra preta literally means in portuguese "black soil", is also known as dark earth and is a type of very dark, fertile anthropogenic soil (anthrosol) found in the Amazon Basin. It is also known as "Amazonian dark earth" or "Indian black earth". A study led by researchers at MIT, the University of Florida, and in Brazil has pieced together results from soil analyses, ethnographic observations, and interviews with modern Indigenous communities, to show that dark earth has been intentionally produced by ancient Amazonians as a way to improve the soil and sustain large and complex societies, given their appreciation for its nutritional base.

Fertile soils such as terra preta show high levels of microorganic activities and other specific characteristics within particular ecosystems. Dark earth also contains huge amounts of stored carbon. As generations worked the soil, for instance by enriching it with scraps of food, charcoal, and waste, the earth accumulated the carbon-rich detritus and kept it locked up for hundreds to thousands of years. Dark earth has the potential to be a powerful, carbon-sequestering soil.

Gardens, even on a small scale, have a notable impact on mitigating climate change through several mechanisms: vegetation acts as a carbon sink, absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide through photosynthesis and storing it in plant tissues and the soil; healthy soil, enriched with organic matter through composting and reduced tillage, sequesters significant amounts of carbon; locally grown food reduces the carbon footprint associated with transportation, processing, and storage of food; and thoughtful plant selection, including native and drought-tolerant species, can decrease water consumption and the need for resource-intensive fertilizers and pesticides. Furthermore, urban gardens can help to cool urban heat islands, improve air quality, and manage stormwater runoff, contributing to more resilient and sustainable urban environments in the face of a changing climate.

Gardens for salvation

"When I take care of the land, I am also taken care of by the land."

- Shennong

There is an urban myth going around these days that billionaires are building bunkers to survive the eventual collapse of civilization. Bunkers can be considered a technology that responds to a paradigm of using the wonders of science and technology for confrontation, separation, isolation, individualism, hoarding, power, inequality, war and dominance. Collective gardens offer an alternative paradigm: one that uses science and technology to bring people together not just among each other but with the local ecological context in which they exist so they can not just survive but thrive.

Collective gardens, in a scenario of societal collapse or crisis, will become spaces for people to come together to share, support each other and get the basic but magical fruits of nature that will allow them to live. Gardens are also cheaper than bunkers, which makes them accessible to non-billionaires. Maybe even more importantly, they are also a way to prevent the collapse of civilization instead of accelerating it like in the case of bunkers that seed mistrust, competition and fear among ourselves.

The analogy or comparison of gardens with bunkers makes us face an uncomfortable scenario, which is the end of civilization, order, or even an apocalyptic world. Paradoxically, when we have the courage to face and accept the impermanence of everything, even what looks stable and permanent, we access a new appreciation for life and the present. Gardens, as a form of post-apocalyptic technology, are not just a survival tool in the case of an extreme situation. They are a technology for living the mundane life that is happening right now in our journey to those future scenarios. The value of the garden, while presented as a tool to survive apocalypse, it relied on actually helping us remember the groundness that we require to survive each mundane moment.

Gardens are also a proven source of health in which nutritious food can be grown, biodiversity restored, water absorbed and consumed and animals and insects can live in a harmonic way. There is an opportunity to partner with local hospitals and other health centers interested in promoting the enhancement of health in the community.

Gardens as a collective cognitive technology. Gardens as collective computers

Gardens, especially community gardens, are collective cognitive systems in which humans, nature and infrastructure are braided with specific context in a form that makes them unique. These collective forms of expressions are computers in the sense that the experiences of each individual interacting with the system is changed in a way that also transforms the identity of the self and the whole simultaneously.

Formal collective gardens

Modern society has been embedded in an information-theoretic era for many decades, so we have come to believe that experience, knowledge and meaning can only be transmitted through a conversion from the material world to the information world. This concept is engrained in all aspects of today’s technology, but the collective computer is fundamentally different. As we conceive of it, a collective computer relies more on experiences and phenomena than analytics, information and language.

The limitations of language have been explored by many, including Ludwig Wittgenstein, who said, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Other researchers have expressed the limitation of analytics and language to compress meaning. Bret Victor, for example, described to the MIT Media Lab a new media for understanding the interplay between perspectives and structures currently outside of our human senses. Other examples include Varela and Maturana, who described knowledge and communication as a biological process instead of an information process.

For collective computers, Claude Shannon’s information theory that posits "meaning is irrelevant to the engineering problem" falls short. The relationship between perspectives and meaning is an ever-changing ecosystem that becomes more complex the more it is examined. In a mysterious way, the more we observe something, the more complex it becomes through its fractal and self-expanding nature. Each time we zoom in to the system, we open little universes of meaning and connections.

Complex systems, like biological and other natural systems, don’t reduce into composable parts. This presents one of the main barriers in expressing the material world purely as information or purely through language and symbols. To effectively manage this ecology of meaning, collective computers must rely on phenomena as they materially combine with one another.

The inability of modern information theory to account for meaning motivated scientists like Joseph Goguen to develop a new type of complexity-based information theory using mathematics like category theory.

Advances in mathematics enable new ways to study fractal structures and relationships found in complex systems. The recursive nature of emerging fields like category theory makes it possible to study the expansion of complexity that occurs when we observe something. For the first time, new mathematics gives us a language to understand patterns of recursiveness and infinite structures in ways that are more systematic and formal.

This math wasn’t available when Shannon’s information theory was being developed in the 1940s because it was also crystallizing into a field of its own. Now that applied category theory is more mature, it’s time to consider fundamentally new ways that meaning can be compressed and transmitted when collective computers come together. We cannot rely on information alone to access the mysterious nature of reality, but we can rely on phenomenon and experiences to compose what is already happening at the material, physical level.

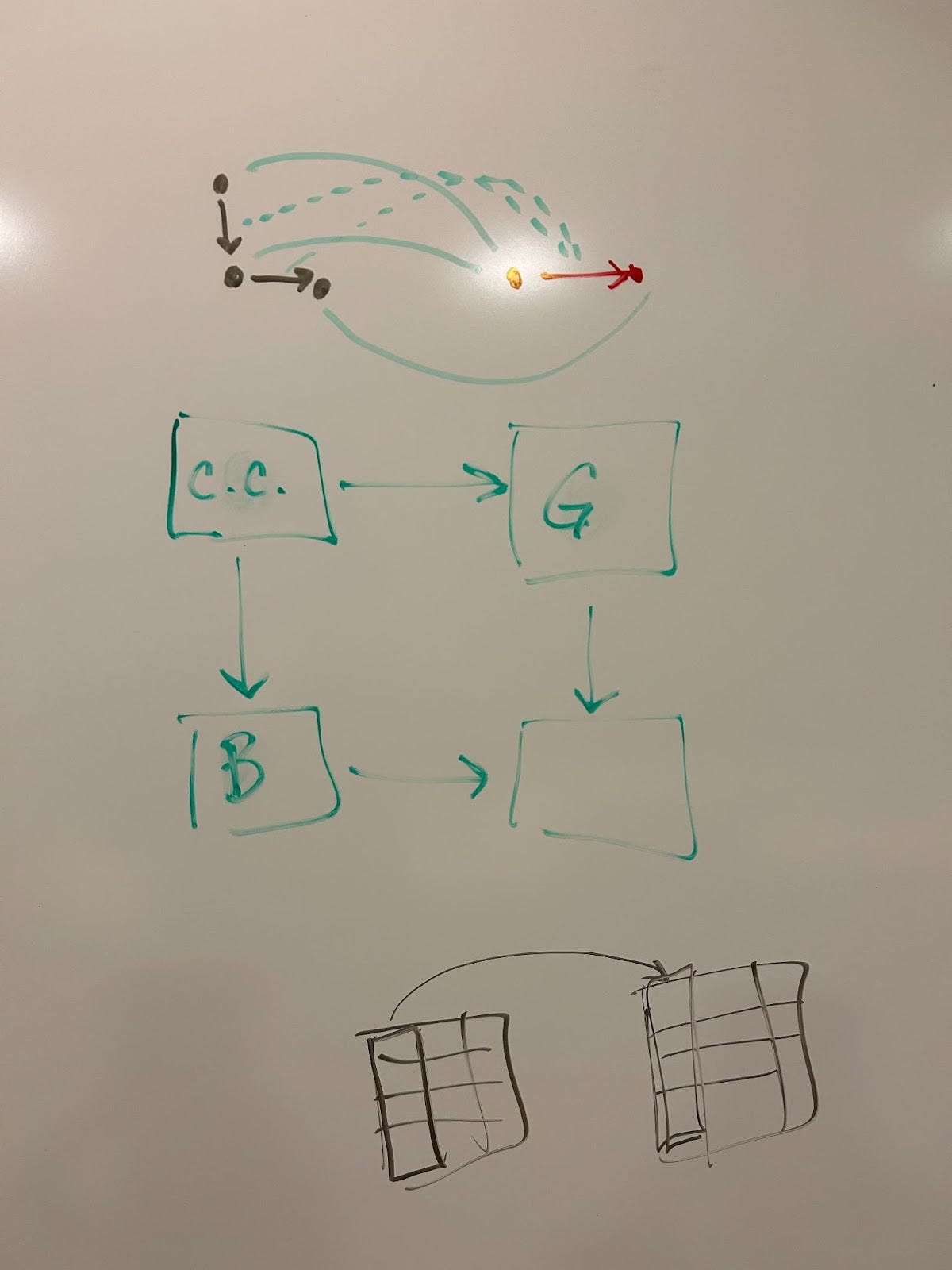

Collective computers can be viewed as a suspension of thinking and expansion of connections. The system architecture is not, like in Von Neumann, designed for inputs and outputs but instead a compositional and relational architecture based on formalisms for matter (material world) and pattern (concepts and mathematics). When matter and patterns meet, compositionality requires connecting material conditions of the world to conceptual patterns and understanding. Mathematicians like David Spivak refer to this language as “coming alive” when it directs material change through compositionality.

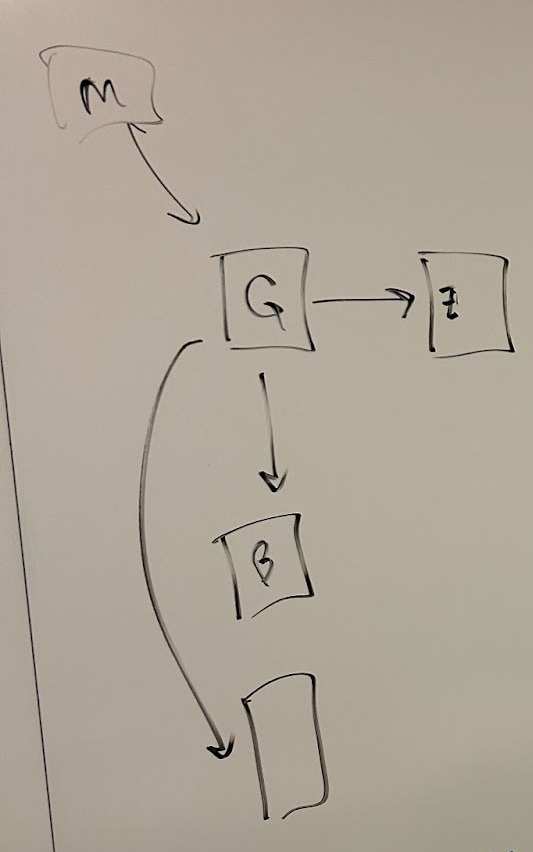

Paraphrasing Malhotra, a collective computer can be a machine or method designed for a collective system like a business that requires a chain of services. This machine will require multiple types of affordances that include diversity of perspective, knowledge transfer, knowledge deliberation or the combination and interlacing of knowledge (knowledge weaving).

a.1. A full-scale board game for neighborhoods: theme, mechanics and experience

Games have been traditionally considered by business executives and decision makers as good metaphors for strategy. The field of Economics has a whole series on game theory, with an extensive history of thinking about decisions as a game with losers and winners, balance and equilibrium and all kinds of agent-based concepts.

Intriguingly but not surprisingly, one of the most influential figures of the 20th century in computer science, John Von Neumann, heavily influenced the development of the economic ideas behind game theory. In 1928 he published the paper “On the Theory of Games of Strategy.” These two seemingly unrelated fields, computer science and economics, have much in common when framed as an approach to deal with understanding cognition and intelligence.

A collective computer is a technology based more on a phenomenological foundation of cognition rather than an analytical one. In this sense, learning from game strategies wouldn’t be enough to influence the computation of a collective computer, because it would lack the actual experience at a material level that belongs to the specific moment in which the computation happens. For the design of a collective computer, it is better to consider not just games as a metaphor for agent-based interactions but games as an actual experience. This means accepting that the phenomena of a game is an expression of a collective computation.

Role-playing games like Dungeons and Dragons, offer a unique analog approach to collective computation that can address the challenges of volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environments in industrial and corporate settings. By providing psychological safety through detached role-playing, these games encourage participants to bring their full selves to decision-making, fostering systems-thinking, exploring alternatives, and managing conflict in a non-personalized way. The inherent randomness and collaborative storytelling within the game structure promote adaptive exploration and the consideration of diverse perspectives, ultimately leading to more harmonious and proactive collective decisions, contrasting with the often siloed and reactive nature of traditional, digitally-driven business problem-solving.

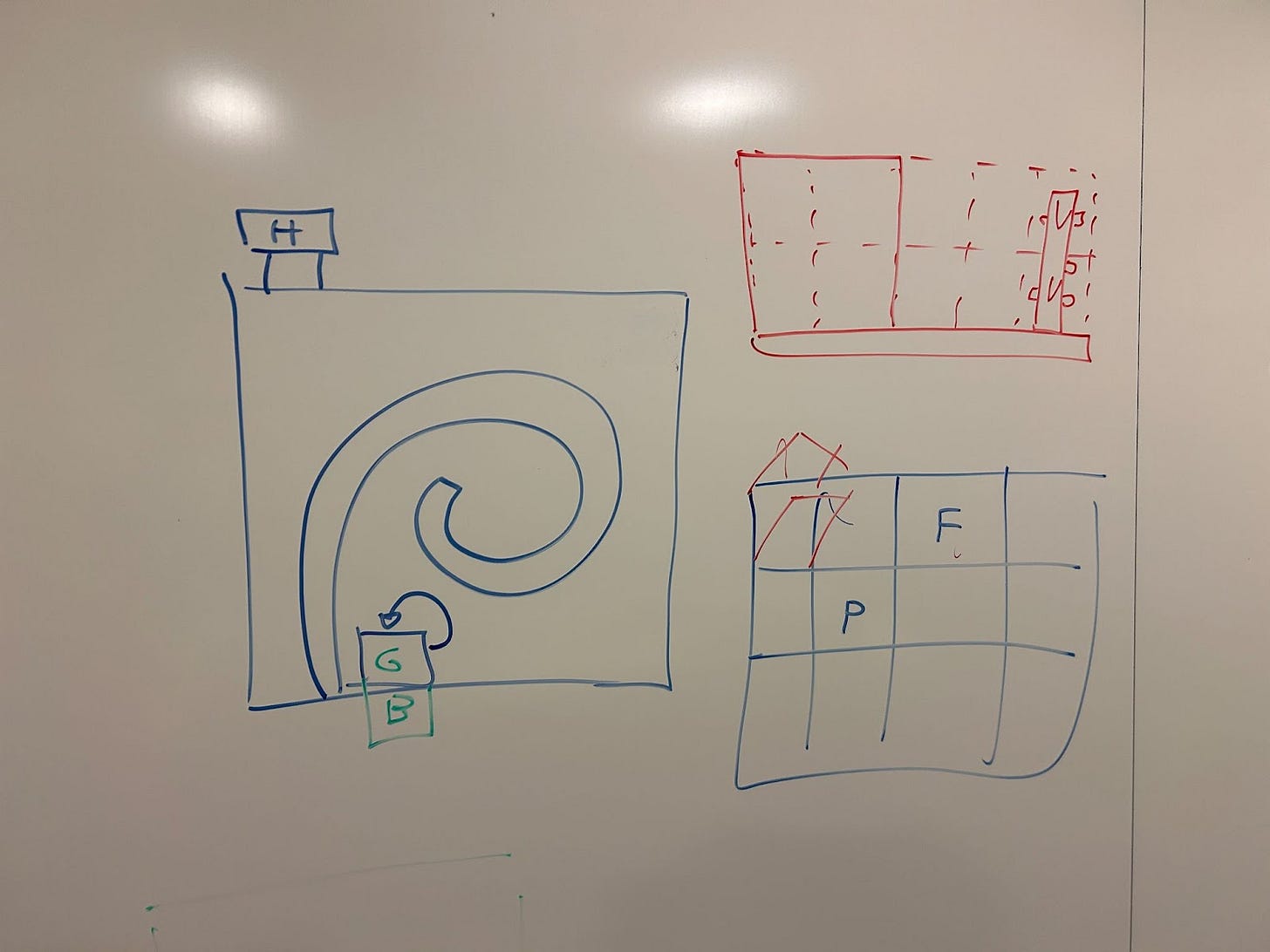

a.2. Experimentation on formality of the gardening mechanics

Community gardens provide the perfect ground for experimentation and the research and development of collective technologies. We are envisioning and testing different concepts of rules and mechanics in the configuration of gardens.

Some of the directions we are taking as we design the mathematical, tacit and operational rules of the collective gardens are:

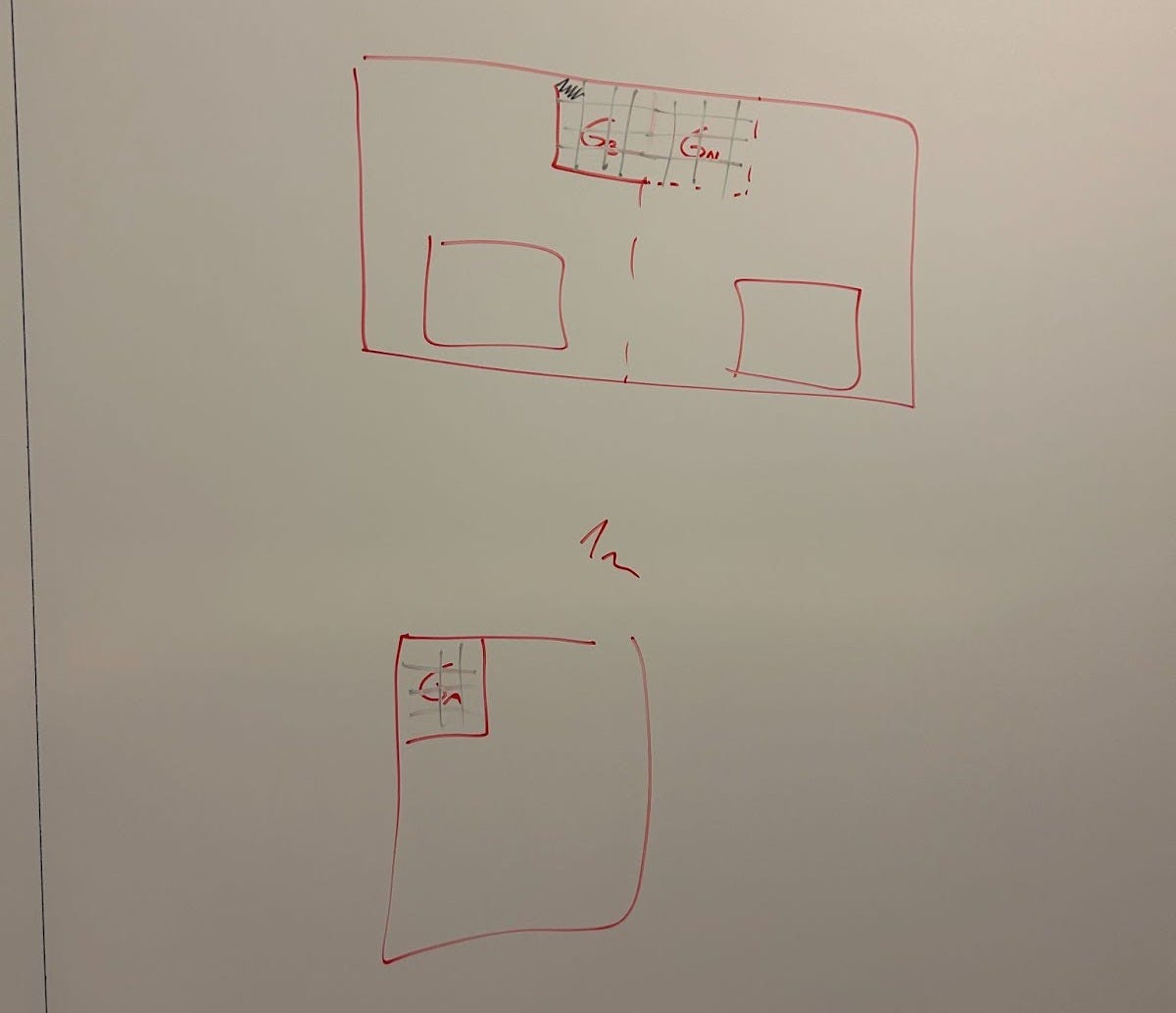

Adjoining or adjacent versus non-adjoining gardens:

We are exploring the rules of gardens within private properties and the role of the scenario of adjacency as it represent a case in which some of the rules change across the border while many of the operations and mechanics are going to be inevitably shared

Compositionality of gardens through colimits

Chain of colimits and composition

Composition of tangible and intangible things

A material database

A set of standard-appropriated formats (compromise for commercial interest)

A composition of material databases, like a material analog version of the categorical database work done by Ryan Wisnesky and others.

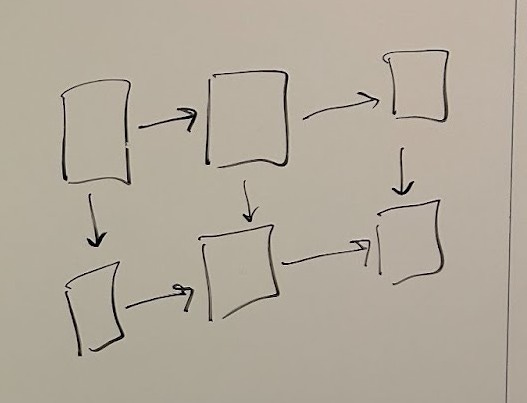

a.3. Categorical / Compositional gardens

Gardens can be arranged in a way that enables compositionality, meaning that the collection of gardens in a neighborhood are able to work collectively. In this section, we describe the background of the mathematics and science behind the concept of achieving compositional gardens through the mathematics of category theory, then extending the idea to the application of non-symbolic math at a neighborhood level, and then we will describe the approach of achieving collective clarity that is the foundation of compositionality through the formal contract of affordances. This section is an explanation of the principles and methods behind the methodology to design and construct gardens.

Gardens can be designed with enacted compositionality, allowing neighborhood gardens to function collectively, a concept explored through the lens of mathematics and science. Capturing meaning from multiple perspectives, crucial for collective systems, is challenging for symbolic methods, suggesting that a phenomenological, experiential, and non-symbolic reframing of mathematics, drawing inspiration from nominalist reconstructions and higher-level mathematical tools like category theory, could pave the way for engineering collective computers focused on relational operations and the formalization of experience.

The core idea is to move beyond traditional computer architecture based on binary code and information processing towards a system that facilitates collective clarity and composition through the formal contract of affordances and non-symbolic value exchange. Instead of relying on fungible symbols like money for transactions, a collective computer could enable the creation and transfer of "crystallizations of value" – snapshots of composable moments of meaning. This shift in focus from accounting units to accounting roles within a decentralized system aims to create a technology that fosters community building and richer interactions by making affordances explicit and enabling a collective sense of "being home," ultimately allowing for a more multidimensional and expansive experience of value and meaning..

Another example of non-symbolic math can be found in traditional match-puzzles that have affordances built into them. The puzzle restricts what can be moved around by only allowing a match at a time, thereby establishing a formalism. The match-puzzle example differs from other symbolic-based formalisms in that it’s achieved through a physical phenomena rather than a set of abstractions and rules.

A mathematician might argue that the match-puzzle can be represented in an abstract way so the problem can be solved easier than interacting intuitively with the matches. Similarly, Leonhard Euler in 1736 presented a solution to The Seven Bridges of Königsberg, which was a notable problem in mathematics, by using an abstract symbolic method that laid the foundations of what is now known as graph theory and prefigured the idea of topology.

A collective computation, however, challenges this premise. Collective computing requires multiple perspectives to come together and share meaning, which is not included in the abstract graph that Euler envisioned. In fact, it is quite the opposite: symbolic representation strips away the meaning from the phenomena to focus exclusively on what matters to answer the specific question from a particular perspective.

An extension of the previous hypothesis is examining whether the type of problems that are difficult or impossible to represent in symbolic mathematical terms are the ones that require capturing meaning from multiple perspectives. Capturing multiple perspectives is an essential characteristic of collective systems, but symbolic methods fail at trying to compose their collective meaning. Famous attempts to convey the meaning of diverse systems include efforts to warn future civilizations—that most likely will not speak our language—of the presence of radioactive waste areas, as their hazardous effects will last longer than our languages and ways of being. This effort is known as the Voyager Golden Record, which is an attempt to convey a message to extraterrestrial, non-human civilizations through a spacecraft launched in 1977. Examples like this can be described as time-capsules that communicate meaning across civilizations separated by time and distance.

But time and space are not the only ways to make meaning unreachable across different perspectives. Another example relevant to our time is the gap of meaning and perspective we see among different biological species on Earth. Scientists are attempting to close this gap by redefining communication in an non-anthropocentric way. Dr. Leroy Little Bear asked during the 2016 Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences in Canada: “What scientific formulas have the fish discovered?” This is a fundamental question for us to consider in order to be collective with other species and other versions of ourselves across time and space.

While the latest examples might seem too extreme or irrelevant to the “pragmatic problems of integrations that modern businesses face,” we believe they are critical and more related than we tend to think. One of the biggest barriers to address integration and composition is that we keep overlooking it as a technical problem. In other words, we tend to assume that talking to aliens is a hard scientific, philosophical and technical problem, but talking to my colleague from a different department? That must be easy!

We use non-symbolic representations at the early stages of development with kids as they learn the basics, and then we assume symbols are better because we are conditioned our whole lives to linearly project things to infinity. Maybe counting fingers is the way to do math in pre-kindergarten, but we don’t have enough fingers to do the math taught in first grade, so we start abstracting and using symbols. We claim that in some instances, especially when meaning should be integrated from multiple perspectives, we could benefit from the use of non-symbolic math.

The discussion about non-symbolic mathematics isn’t new or unique to the efforts of developing a collective computer. Goodman and Quine tried to reformulate theories from natural science without making use of abstract entities (Goodman and Quine 1947), Field made an earnest attempt to carry out a nominalistic reconstruction of Newtonian mechanics (Field 1980), and many other theories have attempted to give a nominalistic reconstruction of mathematics (Burgess and Rosen 1997). In the book A Subject with No Object, Burgess and Rosen argue that it is difficult to account for the possibility of the knowledge of objects like numbers and other mathematical entities as they are exceptional in having no locations in space or time or relations of cause and effect.

A collection of community/private gardens can be arranged in a way that computes the experience of the neighborhood in a material way that is not symbolic.

In a nominalist reconstruction of mathematics, concrete entities (experiential phenomena) will play the role that abstract entities play in platonistic mathematics. These concrete relations (such as chemical bonds or biological relationships) must be used to simulate mathematical relations between objects. We are aware of the challenges that attempting something like this would have given the discretization that quantum mechanics brings to nature (Hilbert 1925). Designing a nominalistic computer would create the need to find the required collection of concrete entities. Furthermore, even if infinitely many concrete objects exist, nominalistic relations would have to prove that they could perform even elementary mathematical theories such as Primitive Recursive Arithmetic (Niebergall 2000).

A collective computer, however, would not be concerned about computations related to traditional mathematical theories like Primitive Recursive Arithmetic. Instead, its focus of attention would be on collective and relational operations in which even the most abstract modern mathematics are still struggling to be effective. Category theory, homotopy type theory or higher topos theory have recently made significant progress to provide tools to reason about composed collective systems. However, the nature of these tools is fundamentally different to the architecture in which traditional computers are designed and operated. Very few applications of these higher forms of mathematics to engineering and society have emerged. This provides a barrier to implement applied versions of truly compositional systems as they have to be simulated or emulated through symbols or software but never really materialized.

This is the main reason why a phenomenological, experiential and non-symbolic reframing of mathematics is of interest to engineering a collective computer in the context of gardening. The aim is not to reconstruct traditional computational operations but to implement new ones that have yet to be realized in today’s computers. In this context, a progression towards formalism of phenomena and experience could be significant in achieving collective computers and composition.

Consider conventional computer architecture in which high or low voltage in a micro transistor is interpreted as a 0 or 1. The computer converts it to information (binary) and then processes it. A collective computer doesn’t have to replace communication, just the transactional nature of what we do, which is basically evaluating things in relation to other things. This removes the need for explicit information-based communication. For example, I don’t need to ask if you can help me if I get stuck on the beach—I can convey the experience non-verbally and do so in a way that is more universal, formal and multimodal.

When paradoxical complexity emerges, we tend to resort to tribalism or rely on a compressive, reductive and fungible concept like money. There is a gap in between that collective computing can occupy to facilitate more rich interactions—a way to keep the tension and create a capacity for people to connect without resorting to symbolic terms. New mathematical phenomenological structures called “collectives” that serve as a new kind of ecological system can be a protocol for reasoning in an expansive way about non-fungible contributions of different members of a collective.

Social and cultural rituals can also be symbolic perceptions (The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present, by Byung-Chul Han). These symbolic perceptions act as a way of feeling safe and as an enabler of collectives and communities. Every moment is nonconceptual on its own, but there is something about symbolic perceptions that makes us feel “home.” If we each have a computer, the first question is “can I trust you?”, which detaches the symbol from a math interpretation and enables a more social level perception.

Another aspect of non-symbolic design is creating a technology that lives between the space of fungibility and commensurability. For two things to be commensurable, they are assumed to be fungible. However, fungibility is not required for things to have the same measure. Trading and financials are central to economic societies. They allow us to experience globalization and industrialization at scale. Money removes the content and meaning from the transaction and makes it scalable versus what trading physical objects would require. In this sense, symbolism is perceived as an advantage that enables modern life.

However, if we had a machine—a collective computer—and were walking into the jungle, the machine itself would become valuable. It’s not how much of a fungible symbol we have, it’s the actual phenomena, experience or thing we are carrying. It’s the phenomenological machine which contains modifiable affordances over time that gives value. An example of this is the capacity to do something through affordances. Others would be able to experience through the machine the capacity of affordances. The collective computer in this case has value because others will want to access its affordances and subsequent value.

As an analogy, for a person driving a car on a beach (which we assume would be even allowed) seeing other cars with hitch receivers would be an explicit affordance that these vehicles can act as a recovery system in the case of getting stuck. Because not all cars have hitches, being close to those cars that do would carry certain value. The physical phenomena is an explicit affordance that certain cars have the capacity to be collective by linking cars to each other through lines and cables.

The practicality of explicit affordances is that they act as phenomenological replacements of symbols that give us a collective feeling of “being home,” which makes us feel safe. If a person is carrying a machine that makes affordances explicit, and others are carrying similar machines, people would be able to feel safe and home in a way, through the affordances described by the technology. Today that happens informally by looking at subjective things like the aesthetics or style. Collective computing allows community building without the need for explicit verbal communication, but in an expansive way, like a ritual would do, and not in a compressing way, like money or information, as in an information theoretic way.

As a symbolic form of value, money is needed in today’s world because we haven’t figured out how to compositionally compare value without commensurability or fungibility. However, this is in conflict with the experience of feeling that life is multidimensional, that meaning is expansive and that time and the present are valuable. We have shortcuts to actualize meaning—money is one way today. The accounting system of economics is money, but a collective computer would require changing that for a decentralized system where instead of focusing on the accounting unit we are focusing on the accounting role (the computer). We are changing from the “what” to the “how.”

Imagining that we have a non-symbolic transaction or experience is a first step for conceiving a collective computer—it doesn’t have to be translated to money—as long as we can formalize and respect it, assuming we have a computer to do just that. David Spivak says it’s a crystallization of a value—a snapshot. The computer can take a picture of a composable moment of value (meaning). Instead of transactions, we collectively create crystallizations of value that are transferable and compositional.

a.4. Gardens as the memory of a neighborhood

The narrator of Moment 7 describes how the syms, as collective computers, acknowledge the composition of all things—chains upon chains of connections, near and far. This idea hearkens back to mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage (1791–1871), who believed “the air itself is one vast library on whose pages are for ever written all that man has ever said or woman whispered” (Babbage, 1837). Babbage’s idea was grounded in the notion that all phenomena are related to each other and that, by consequence, the inseparable connections produce specific conditions in the air of the present moment as causality of the memory itself (Robins 2016b). In other words, there is a material aspect of systems: “as a process unfolds in time it leaves behind a material history of effects on the world” (Nester 2023).

Landscapes, maps and memorials are compositions of memories created to capture, store, remind and commemorate. To understand the connectivity in human-landscape ecosystems, a multidirectional concept of landscape transformation, sociocultural development, and human response cycles needs to be considered. In this context, societal decision-making is controlled by the ecosystem’s functionality: the human perception, experience, memory and tradition as well as the individual configuration of landscape components, which are a conceptual framework herein referred to as landscape affordances.

Affordances are not only potential decision arrangements in the life track of organisms. They can also generate conglomerations of attractions or repulsions that influence an agent’s behavior and thus make an impact on the composition of future affordances (Withagen et al. 2017). Affordance sequences can be created that accompany an individual’s decision-making. Because decision-making directly affects the individual’s social environment and his/her descendants, the affordance arrangements are passed on over time and space.

The concept of composing affordances can be viewed as a way of understanding the specific existence of each moment as a trace of all the past histories that led to it. This aligns with the concept of memory traces (De Brigard 2014), and, in the case of a collective computer, the memory formed by composing individual computers becomes a map of recent history. These chains of affordances act as a trail of contexts and serve as a reminder that all life forms are in fact processes and not things. The “me” of five years ago is made from different stuff than the “me” of today. Composition is an event that never stops. We are really just systems through which matter is continually passing.

The collective computer allows humans—and nature—to express affordances using a new interactive channel, arranged and rearranged in such a way that it can be interpreted by others with enhanced clarity and awareness. This ability to interpret the perspectives of others enables the negotiation of complex tradeoffs and relationships as a collective. Collective computers can report changes to affordances and create a shared awareness in ways that are inaccessible and impossible with today’s information theoretic technologies.

Imagine that rather than choosing one perspective or another in a coin flip, we could reason about both. It’s inconceivable to hold multiple viewpoints in our minds at once, yet this happens in nature all the time. When faced with a metaphysical fork in the road, the collective computer isn’t forced to choose one path or the other. It can branch and take both routes to explore new spaces of meaning. One perspective becomes two, becomes four, becomes eight—yet all remain connected to one computational network. Is this computer singular or plural? Somehow, improbably, it is both and more.

Developing a collective phenomenological computer requires an understanding of memory in relation to cognition, collectivism and phenomenology. It also requires examining the current conventional approach to defining memory in computer science so that a new theory and paradigm of collective computational memory can arise.

A significant contribution of the collective computer is to progress the concept of memory in computer science and engineering, specifically as an emergent property of collective systems. Michael Levin posits that all intelligences are collective, but what about collective forms of memory? Today, the concept of collective memory for computer scientists is the addition of storage capacity. However, collective memory could be something that enhances other aspects of memory. By creating systems that are distributed and decentralized, the collective computer can eliminate the need for a component that produces this storage, allowing instead the structure itself to be the storage.

Collective computers also address another challenge with the concept of memory in conventional computer science. That is, if we create something collectively, who stores it? If the answer is both parties, how do they resolve the consistency of who stores it and which transistor it goes to? This uncertainty is resolved when memory is an emergent property of the collective systems coming together, as with collective computers. By the fact that individual collective computers are composed together, the memory can emerge.

The main defining characteristics of the new paradigm of memory required to conceive and architect a collective computer are:

Memory is more than just the storage and retrieval of a deterministic state of reality. It is a complex cognitive process that involves the metaphysics of memory or a theory of remembering applied to computation. A conventional computer needs to store a deterministic piece of information and retrieve it for use. However, in general these aren’t required for collective memory. Memory neither needs to be retrievable or represented in a way that is describable. It can be probabilistic and metaphysical. In a conventional computer a transistor stores a 0 or 1; this becomes a binary, deterministic fact. In this way, memory is defined by high or low voltage as stored phenomena. There's no uncertainty to it, unlike memories in humans and biological systems, which provide clues about the significance of this to cognition. Natural systems, on the other hand, have a high degree of uncertainty.

Declarative memory, in general, is divided into episodic memory, corresponding roughly to recollective memory, and semantic memory, corresponding roughly to propositional memory (Broad (1925) and Furlong (1951)). Conventional computers mostly address episodic/recollective memory given their incapacity to store meaning in a binary information theoretic architecture. Episodic memory, the memory of writing or reading words, combined with a semantic memory, remembering the meaning of these words, can be a useful distinction when architecting a collective computer.

While memory itself is one aspect of computing, another is reasoning about the memory itself. Conventional computers lack this self-reflective nature. Advances in category theory—with mathematical machinery like the identity function and endofunctors—make it possible to reason formally in a self-reflective way about specific mathematical contexts.

Conventional personal computers are based on the general conception of a Turing Machine as the highest form of automata. An assumption for this theoretical machine is that the tape is infinite, meaning a Turing Machine is not feasible in practice. This leaves us in the real world with only limited versions of Turing’s idealized automata.

Given the limitations of declarative memory to capture reality, a collective computer should consider non-declarative forms of memory as experiential and phenomenological.

There is material relevance in the relationship between memory and imagination, simulation and cognitive time-travel (Debus 2014; Perrin and Michaelian 2017).

Recent research has provided contributions and progress on the understanding of external memory in cognitive science, which views remembering through the lens of distributed (Hutchins 1995) or extended (Clark and Chalmers 1998) theories of cognition.

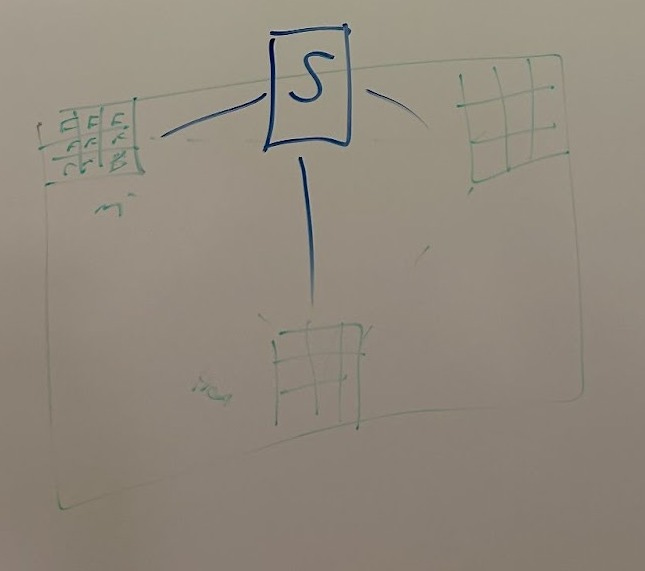

a.5. community gardens as collective formal contract of affordances

“They don’t understand what it is to be awake, To be living on several planes at once Though one cannot speak with several voices at once.”

T.S. Eliot, The Family Reunion

A collective system like community collective gardens will necessarily have multiple affordances relating to each other. A collage of perspectives, capabilities and boundaries define what is possible or available in a particular context for each individual and for the collective as a whole. These affordances are diverse and complex, relating to each other in ways that determine individual and collective behavior. In this sense, individual and collective behavior is a result of what is possible based on a composition of affordances.

From an individual perspective, the function and objective of a system could be relevant to determine behavior. For a collective system these concepts overlap and compose into something not always reachable by language. In other words, the composition of affordances is only observable through emergent behavior. Andrea Hiott generalizes this notion by calling it “trajectory.” The trajectory of an individual system is a more abstract form of a destination, objective or function that the system is performing. An individual perspective of a trajectory is individualistic by definition in that it dissolves into something different when looked at from a collective point of view.

For a trajectory to be called individual and collective we first have to define, in the words of Andrea Hiott, “a measure that is using assumed terms specific to the measurer and their lifeworld. For the measurer, these set parameters will make whatever is being observed seem to have a beginning and end. Nestedness does not begin or end but only changes dimension and form because there are no gaps, only changes of position.” From each position a different measure of individual will emerge and establish the trajectory. Therefore, an individual trajectory is observed from a specific position and measure of nestedness.

In contrast, a collective trajectory that simultaneously considers multiple individual trajectories,positions or measures from which to observe a system's way-making can be considered a form of cognition. This presents a dichotomy of individual and collective. A trajectory can be observed for any chosen position or measure of a system.

When more than one position or measure is established, the emergence of multiple trajectories will produce apparent and real conflict, disagreement, friction, tension and many other forms of “encounters”, using the language of Andrea Hiott. These encounters are multidimensional in that they can be emotional, psychological, logical, physical, chemical, biological, temporal, etc.

These encounters, from a specific position and measurer’s point of view, can manifest themselves in the form of arguably undesirable experiences. To list a few:

Conflicts

Concealed context (when an encounter contains intentional asymmetric clarity between the different perspectives)

Confused or misunderstood information

Force or restrain

Negligence

Expiration

Ignorance

Adam Smith, famous for The Wealth of Nations in which he lays the foundation of capitalism and individualism, is also the author of a lesser known book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In this work he describes a scenario in which, if one knew that a catastrophe was to befall another country, they might be troubled but wouldn’t lose sleep over it. But if one knew they were going to lose a finger, they would be distraught and frantic over the individual incident.

This story points to the apparent dichotomy between problem solving on an individual basis, which we do all the time, and problem solving collectively. In general, problem solving is the idea that we act in response to individual problems that are presented to us for which we have to find a solution, like avoiding obstacles and dealing with encounters. There are multiple reasons why the problem-solving paradigm should be reconsidered in the context of designing collective systems.

The first argument is that the more complex the system the less effective a problem-solving paradigm becomes. A deeper examination at a systems level of problems and solutions inevitably ends in the conclusion that nothing is purely a problem nor a solution. In other words, every solution creates new problems, and every problem comes from the solution that someone else created.

Consider an everyday example like tax structures. The International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (IFRS) is principles-based while Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) are rules based. Even in accounting, it can be hard to define all the rules. In Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous (VUCA) environments, defining the rules is not always possible. Everything is connected, so isolating our attention to just one relationship in a vast network prevents us from seeing the big picture in a more comprehensive way.

The second argument against problem solving is that it reduces the definition of value to a productive or utilitarian perspective. Most financial valuation methods are based on estimating what a financial entity can do. In this case, the primary concern is the capacity of an asset to generate cash flow via income or impact markets in measurable ways. These methods of valuation fail to make sense to the valuation of entities like pieces of art, since art doesn't produce anything directly. Why is some art so expensive if it doesn’t produce any cash flow to the owner?

A systems-perspective of natural complex systems points to entities being not only concerned about what they do but also about what they are. We humans care not only about “doing” but also about “being.” These are important aspects of decision-making often overlooked when building robotic or autonomous systems, but they are critical as core considerations of morality, vision, commitment and many other priorities for human and biological decision-makers. Because we lack the mathematical expressions to value “being,” we resort to valuing that we can measure—another aspect of what we are doing.

By overlooking the “being” part of a digital solution, we build systems that are not adaptable or composable with other systems. The representation of “doing” is what most modelers associate to the function of the model. Modern computer scientists and technologists, like Donald Thompson, argue that knowledge exists for a specific purpose and, therefore, knowledge that is not useful should not be included in a mathematical or computer model. We argue that, for a collective computer to achieve compositionality, knowledge that has been considered “useless” will act as connective tissue like that in an animal body, with no other purpose than providing connection between specifically designed models of functionality, or organs.

For collective computing, this connective tissue includes individual and collective affordances. A technical challenge, then, is to design for the harmonization of collective affordances. Why?

The intervention and incitement of experiences based on a particular or individual objective could be perceived as an aggression from another individual’s perspective.

Nature is a complex system in action with no obvious objective or goal.

It is impossible to assess the value of an objective for another individual or for ourselves in most cases. An example of this are transformative experiences (L.A. Paul, 2014) like the value of being a parent, in which the “single self” cannot cognitively evaluate the experience of the “parent self” because it is a different person altogether that becomes transformed by the experience of having a child.

The actions performed to achieve an objective can be counter-productive.

A collective computer’s actions and functions are determined by the affordances of the collective in specific contexts that shape experience. The collective computer can be a technology that can help or “get out of the way” of collective way-making though:

Revealing affordances

Intervening affordances

Verifying affordances

Tracing affordances

Inciting affordances

Signaling affordances

Maintaining affordances

Translating affordances

Holding paradoxical affordances (transcending dichotomies)

Reflecting inter- and intra-positions for way-making

Negotiating affordances

Resolving affordances

Collectively computing affordances requires composing them materially and mindfully. Compositionality, taken from Frege’s principle, is the notion that the meaning of a complex system is determined by (1) the meaning of its constituent components and (2) the rules for how those components are combined. Composition describes how complex gadgets, such as affordances, can be assembled out of their individual parts.

This way of thinking about composition of affordances and experiences as the basis for a collective computer defies decades of paradigms about computing. A prominent example instantiated in today’s computers is the belief that the mind is separate from the body. We rely on traditional machines to extend our minds because we believe doing so results in a better outcome.

In contrast, collective computers can be viewed as a suspension of thinking and expansion of connections. The system architecture is not, like in Von Neumann, designed for inputs and outputs but instead a compositional and relational architecture based on formalisms for matter (material world) and pattern (concepts and mathematics). When matter and patterns meet, compositionality requires connecting material conditions of the world to conceptual patterns and understanding. Mathematicians like David Spivak refer to this language as “coming alive” when it directs material change through compositionality.

In recent years, a new branch of mathematics called applied category theory has emerged as a language to formally describe composition. Category theory was originally created to scaffold ideas and transport them across various domains of pure mathematics. This interoperability makes it an ideal formal language to guide and coordinate the collective structures that emerge from individual affordances coming together in a continual commingling. In other words, category theory acts like a meta language—a language systems can use to talk about themselves and to interact with other systems.

Paraphrasing Malhotra, a collective computer can be a machine or method designed for a collective system like a business that requires a chain of services. This machine will require multiple types of affordances that include diversity of perspective, knowledge transfer, knowledge deliberation or the combination and interlacing of knowledge (knowledge weaving).

Gardens: A material computer

A categorical computer is achieved in a material implementation, meaning that it is not a digital implementation on a digital computer but a completely new machine that is natively non-necessarily digital.

The form and function of our urban spaces have always been influenced by technology, from buildings and materials to methods of construction. This includes infrastructure, modes of transportation, communication systems, safety and security, utilities, energy systems, entertainment and other aspects of urban spaces. Even architectural features that now are aesthetic symbols of eras and cultures, like arcs, bridges or walls, have been influenced and determined by the available technologies of the time.

The specific relationship between computing technologies and urbanism is particularly interesting for conceptualizing a collective computer. For a computer to be truly collective, it has to be integrated with its environment. In modern times this would most likely mean the cities and urban infrastructure in which the collective computers exist.

Traditional personal computers connected to each other through the internet are influencing existing urban areas in multiple ways, some of the most notable ones being:

Data centers are occupying physical spaces within urban centers.

Communication infrastructure like antennas and cables create connections between users.

Energy systems are required to power computing systems.

Increased attempts to automate systems are modifying human-machine interfaces and basic infrastructure.

The tendency to invest in making cities “smart” has exponentially increased the presence of physical systems like networks of information systems, sensors and screens.

Surveillance systems have proliferated in multiple forms, including centralized and decentralized instantiations depending on the country, culture and government.

As communication has moved to be mobile and personal, public infrastructure like phone booths has disappeared.

Transportation and hospitality systems have been disrupted by the emergence of a sharing economy driven by computing power that enables near-real time optimization and allocation of resources.

Computing has allowed architects to achieve new types of buildings that were previously too complex to be envisioned through the use of tools like computer-aided design (CAD).

These influences of conventional computing on infrastructure have entrenched architectural paradigms in a way that is difficult to change. Before we could experience the obsolescence of hardware on our desks, but modern data centers have done away with such observations. Now we are digging a hole deeper in obsolescence as the cyber-physical infrastructure becomes increasingly connected. Instead of swapping the monarch in the center of the country to enact a paradigm change, we now have to change our whole cities.

Despite their influence, computers have historically struggled to help architects and urbanists consider the collective implications of the systems they build, from basic problems of lifecycle and circularity analysis to more complex consequences like the social behavior or health of inhabitants. Simulation tools have allowed advanced representations of the implication of urban designs on other complex systems, like ventilation, water dynamics, and many others, but they still don’t match the actual phenomenological experience that buildings create over the ecosystems and social systems in which they exist.

One example of a highly successful simulation tool is the Bay Model, an enormous working model of the San Francisco Bay that includes surrounding river deltas and regular tide changes. Built by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1956, the Bay model acted as a way to do hybrid (computer/physical) modeling where the model is a testbed to demonstrate what happens if dams and infills were constructed in the Bay. Other capabilities of the model include validating theories around climate change, water supply, habitat, land use, flood control and various disasters over a long lifecycle. The uniqueness of this 1.5 acre 3D hydraulic model was in its use as a physical and analog computing to assess the impact of human-made interventions.

Ultimately, the budget for the physical Bay Model was cut in 2000 as it was replaced by a purely digital computer model. This, along with the broader trend of digitalization, doesn't diminish the necessity of formal composition of analog / hybrid systems (e.g., physical-digital) to more comprehensively address the network implications of collective systems within urban settings. The behavioral modularization of physical synthesis for digital computing that arguably ushered in the information-theoretic technology revolution has proven much harder to achieve for analog computing technology. This is a key motivation to consider approaches to architect computers with languages like category theory to study composition of physical systems.

Ursula K. Le Guin said that “technology is the active human interface with the material world.” We expand this notion by claiming that urban spaces—as a technology in and of themselves—are another interface many have with the material world. The shared spaces we find within cities themselves become artifacts, which points towards a kind of shared collective infrastructural system.

Relevant to this idea is a description of aspects about infrastructure from Professor of Engineering Deb Chachra. One aspect is that infrastructures are how a society copes with the material realities in which it is immersed. The other is that infrastructure is not what we normally think of when we think about technology; we tend to go straight to a digital world and its dematerialization in which everything's going to be online.

Infrastructure is a technology that exists as a reminder of basic realities we tend to take for granted. Infrastructure fulfills basic necessities in a way we almost never have to think about. We have built collective systems like water and sewage that allows freedom to lead the kind of lives we have without worrying about water-carried diseases (excluding heart breaking exceptions like in Flint, Michigan and many other places), or even water-availability.

All of these infrastructural networks, especially the energy network from which we all benefit, are to some extent based on a utilitarian philosophy. This mindset means that the infrastructure networks attempt to provide the greatest good for the greatest number of people. However, this has historically disregarded two consequences associated with the rise of these networks.

First, any network that brings resources from someplace else is also taking resources away from that same place. Second, infrastructure networks can also be used to mitigate harm and displace them with benefits in a way that tends to be unevenly distributed. This begs the question of who makes decisions about the allocation of benefits and harm.

Chachra describes in her book How Infrastructure Works - Inside the Systems That Shape Our World six actionable principles for a new type of infrastructure systems. These principles can be directly applied to the concept of infrastructure as a form of collective computer:

Abundant energy and finite materials: We are surrounded and fulfilled by energy but limited in the access to the materials that allow us to dispose of it as traditional industrialization has allowed. The collective computer will be enabled by a new paradigm of energy as a system, taking inspiration from biological processes like endosymbiosis, regeneration and harmony.

Design for resilience: As complexity increases, the likelihood and consequences of catastrophic events will increase. The collective computer will adapt to significant events as a form of cognition, transcending moments of material change by preserving life.

Build for flexibility: Uncertainty and change will accelerate adaptations as systems withstand alterations of their context and structures. The collective computer will adapt not only to big events in the form of resilience but to any change and any use in a self-reflective pattern of realization.

An ethics of care: As societies and ecosystems become intertwined in ways we don’t fully understand, caring will be essential to interconnected systems. This is especially true of the collective computers based on respecting affordance of other entities. Caring means, for a collective computer, the respect of boundaries in the form of affordances.

Recognize, prioritize, and defend non-monetary benefits: A move towards non-fungibility of socio-economic systems is critical to their realization.

Make it public: The collective computer is public by definition. This expands concepts of property and ownership, which are limited to an individualistic foundation which is not collective by nature.

Chacra goes on to describe how infrastructure can be used as a measure of power, freedom and “value” in an expansive way, because it is the intersection between freedom and cognitive capacity, which depends on the infrastructure that is in place. The tricky part is that these systems are all collective, so we can’t measure or directly connect units of value to a specific perspective of entities as a relationship to those systems because they are completely collective. In other words, it makes no sense to try to isolate metrics at an individual level that are collective in structure and behavior.

Collective infrastructure systems—say, a highway—also change as they are used. In regenerative terms: we could replace the value in monetary terms with the capacity to regenerate a system. Collective computers must figure out how to materialize this, but with the dimensions of value increasing instead of being reduced to a single way of valuing something.

Urban infrastructure and building architecture provides semi-formal constraints for nature, allowing humans to behave in intentional ways and act as computers of experiences and phenomena. This has the potential to influence behaviors, relationships, and collective way-making in general. Cities are related to cultures and ecological contexts and to times and eras. In many ways these computations are unintentional, but in some cases cities and urban spaces can be intentionally designed to perform certain phenomena—to compute collectively.

A non-human user experience

Gardens have historically being spaces in where humans attempt to control and enclose nature, however, they are also home to complex systems of many insects, worms, fungi, bacteria, plant, sometimes fish, animals, birds and all forms of living and non-living entities.